By Prof Costas Papazachos*

Monitoring the Santorini volcano : Seeking answers for the future by looking into the past

Since antiquity, the relation between humans and volcanoes has always been controlled by the anxiety of the next volcanic crisis. The underlying question of the next volcanic eruption is fundamental, especially for volcanoes that host large human societies like Vezuvius, Santorini, etc. For the largest time period that humans live on this planet, the answer to this question relied on the fact that volcanoes usually exhibit a large variety of precursory phenomena (intense seismicity, gas emissions, changes of landscape and morphology, etc.), which allowed civilizations since antiquity to detect in many cases (though not all) an impending volcanic eruption.

With the development of science, the first geoscientists realized that it was not possible to do much more regarding the possibility to predict the next major volcanic eruption. As usually happens in this case, since they could not predict the future, they turned their attention to the past history of volcanoes. This decision proved to be of extreme importance, since it allowed new generations of geoscientists to study and understand (even partly) the mechanisms that control the way volcanoes behave, the time patterns of the eruptions and evaluate their impact on the natural and man-made environment. However, with the dawn of the modern technology revolution era towards the end of the 20th century, a large number of new instrumental tools became available for the study of the volcanoes, allowing the use of advanced monitoring networks that can quite efficiently provide warnings for forthcoming volcanic eruptions.

Santorini was no exception regarding the previous process. While tens of geologists and volcanologists have studied (and still study!) the history of the Santorini volcano, the use of monitoring networks delayed excessively. While initial efforts started in the 70s, the only systematic monitoring approach was realized by the Institute for the Study of the Santorini Volcano (ISMOSAV), where scientists from various Greek and International agencies met, in order to install and operate a permanent monitoring network of the Santorini volcano. This network comprised of seismographs for the seismicity monitoring, GPS and tide gauges, as well as a CO2 gas real-tine monitoring system on Nea Kameni. This network between 1995-2010 defined the “equilibrium” level of the volcano, in other words the permanent level of its seismovolcanic activity. This effort was supported by periodical measurements using dense temporary geodetic (mainly GPS), geochemical and seismological networks.

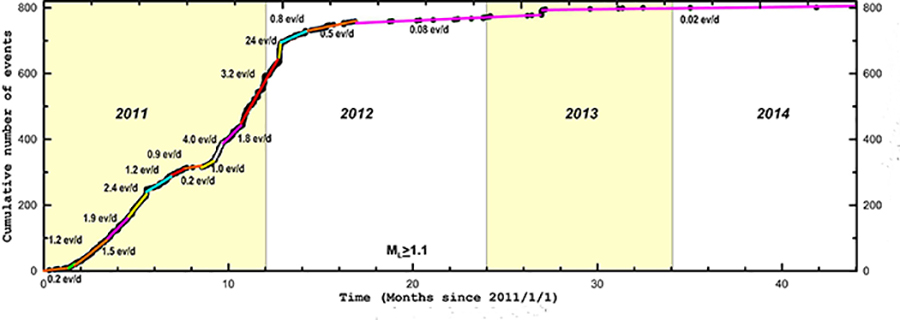

The importance to have an operating permanent monitoring network became evident in the beginning of 2011, when the network detected the initiation and monitored the evolution of the small seismovolcanic crisis of 2011-2012. In figure below we show the time evolution of the seismic activity in the inner Santorini caldera area for years 2011-2012, as well as during the following two years (2013-2014). It is evident that the activity started in the beginning of 2011, exhibited several peaks and troughs, and practically faded-out in the spring of 2012. Studies of several groups showed that this seismicity was accompanied by intense deformation (detected with geodetic and satellite data), as well as intense geochemical-geophysical anomalies (increase of H2 gasses and sea temperature in regions and periods of intense activity). This multi-parametric monitoring allowed to reliably evaluate the crisis evolution, which shows the importance of instrumental monitoring for the assessment of future volcanic eruptions, long before they actually occur.

Today (Jan 2017), after the 2011-2012 crisis, several additional advanced monitoring systems have been installed in Santorini, securing its reliable monitoring. Perhaps the only challenge for scientists is the test of time on these networks, since volcanoes are known to remain “dormant” for lone time periods (e.g. decades in Santorini) before they wake up for the next big volcanic crisis.

* Costas Papazachos, Professor of Geophysics, Geophysical Laboratory, University of Thessaloniki